This is a casual piece about my views on behaviourism in general, and my own lived-experience of accumulated trauma and vulnerability as a consequence. It is not an academic article, so I have not provided citations, though the reader can easily find supporting evidence using Google to do a search where interested.

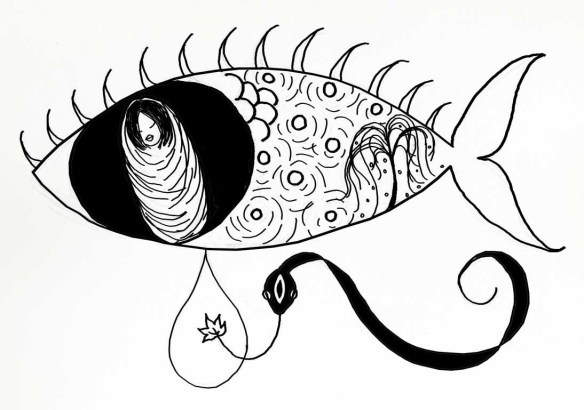

My strong objection to programmes like ABA and all those behaviour-focused interventions that try to rigorously train Autistic people into mimicking acceptable normative behaviour, and unquestioning compliance to normative societal systems, is not only because they are generally hideously abusive and de-humanising, but more crucially devastating in practice, in my opinion and lived-experience, is the longterm, far-reaching harm that these programmes do to the organic, intrinsic functionality of the Autistic human at the very core. The Autistic person is violently cut away from their natural, unique instincts, and forced to adopt superficial behaviours that do not support the Autistic in any deeper meaningful way, leaving them incapacitated, quietly languishing, silently roaring, weeping in despair and grappling with hapless rage, captive subaltern inside the nauseating swirl of normative Neurocolonialism. It is therefore not surprising to find that the majority of Autistic persons who have grown up receiving ABA now report symptoms of Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

I never went through official ABA. I belong to what they call the “lost generation” of Autistic and Neurodivergent people. Nevertheless, behaviourism was a stronghold in my day. I was mocked at, punished, beaten, fiercely berated by parents, teachers and even older siblings, simply for being different. I was repeatedly pronounced “recalcitrant”, told that I would end up in hell if I do not change my “bad, rebellious behaviour”, and coerced into learning how to “behave” according to their expectations and dictates. As a result, I applied myself vigorously to this quest because I (variously) feared getting into even more trouble, or I hoped they’d simply stop and leave me alone, or I wanted to please them. However, their goal-posts seemed to be in a constant state of flux, there were no consistent boundaries and strategies to their demands for “compliant behaviour”. Hence, no amount of effort on my part ever brought the happy results I had desperately hoped for. To this day, I still have not figured out how to please my detractors such that they would stop castigating me in some way or other — but the difference now is that I do not care anymore.

The truth is, it took me many years of meticulous un-learning, effortful self-discovery and determined self-acceptance, finding support from my Neurokin and other loyal friends, and most crucially, a meek, yet majestic canine Angel, Lucy Like-a-Charm, my channel of Divine Grace, to attain all the visible worldly achievements that I have thus far, and become who I am today. I am still struggling to heal from years of trauma at the violent hands of Behaviourism, even if not officially labelled ABA. Lucy, my light and joy, was a humble yet magnificent rescued former racing Greyhound from Australia. I adopted Lucy as a companion pet dog in 2012, the first year of my PhD candidature, but she became, of her own accord, my Autism Assistance Dog, despite never having had prior intensive training. She was also my creative muse who directly influenced my PhD dissertation on autism and alternative empathic resonance, and the Love of My Life, nonpareil.

Success story?

Normative society now likes to tell me, very often accompanied by almost comedic, dramatic gasps, perhaps well-meaning but nevertheless deeply disturbing:

“But you don’t look Autistic at all! Gosh you are so socially polished and so normal!”

Some parents even tell me, with tears in their eyes,

“I wish my Autistic child were like you!”

I am not offended by these parents, rather, it breaks my heart in a way that words cannot explain.

Variations on the same theme appear in social situations whenever I am among strangers or newly introduced non-autistic / non-neurodivergent company. It has become a part of my life, whether I like it or not, and I have learned to cope with this with as much equanimity and humour as I can possibly muster. If I have the energy, I try to gently educate them, but if I am running low on that extra “normative-social-oomph”, I simply smile and change the subject or remain silent. Inevitably, I return home afterwards and have to take painkillers and all kinds of medications to quell the side effects of normative ignorance on my frayed nerves and hyper senses.

Sometimes, when the normative ask me how I became so “socially adept”, I briefly explain that I have always loved the arts, and I loved the old MGM musicals. Ironically, I learned much of what I thought at the time was normative “social behaviour” from the amazing Doris Day, who was my human hero. (I had other heroes, but they were not human, like the spunky rat, Miss Bianca, the spider Charlotte in Charlotte’s Web, the animals in Winnie the Pooh, etc, long before Disney came along and contorted all of them into sickly sweet palatable dessert dishes.) Doris Day wasn’t considered particularly attractive in her time, which made her an “attainable” role model for me, because I was repeatedly told that I was ugly, and I was drawn to her spirit, which somehow managed to emerge in every different role she played. She also sang beautifully, I loved her subtle expressivity — for many years, I was told I had no voice, no talent for singing, so I admired Doris Day all the more. I would secretly practice social behaviour in front of the mirror. Secretly, because if anyone knew, I would most definitely be subjected to endless cruel mockery. I thus became an expert at “performing the unnatural as naturally as possible” — a phrase coined by me some years ago which I employed in my PhD dissertation, my own theatrical take on the by now well-documented phenomenon of autistic “masking”. In fact, my “amazing” stage persona has become so inextricably intertwined with my inner self after decades of intense practice that there is now no way to extricate one from the other anymore. The “auto switch” flips on the moment I step outside of the sanctuary of my own Clement Space. Perhaps the only mortal entity who truly understood and witnessed my “authentic” Autistic self was Lucy Like-a-Charm.

Doesn’t my apparent social ability make me a huge “success story” where behaviourism is concerned? Perhaps I should be hailed the superstar of ABA-like approaches? However, my truth is more sinister than even what the popular Autistic advocates and activists rage about. And I am quite certain many countless Autistic adults would nod knowingly at what I am about to try and explicate.

You see, it is all a grand performance, for which I have won many awards in the normative realm as well as Autistic and disabled domains. I can easily become the life of the party, any party, if I made the effort to be. I show no signs of discomfort in large social events (the key word is, “show”). Yes, people may think I am somewhat “eccentric” but they usually simply think, “Aren’t all intelligent and talented people a little out of the ordinary, anyway?” I am also an engaging professional speaker. I remember one occasion, many years ago, after delivering an animated lecture and discussion session with a group of special education teachers all with Masters degrees, two of them actually told me they did not believe I am Autistic. They said with great conviction and self-appointed authority, “You’re just exceptionally bright, that is all.” I was flabbergasted, but did not respond at the time. (It was night time, I was tired, the performance was over, and I just wanted to go home, take my meds and cuddle with Lucy.)

Since my official diagnosis and finding my Autistic identity in my 40s, I have attained “success” in many highly visible areas of life and living: I graduated with top honours in both my MPhil and PhD (albeit late in life, but the reason for the length of this journey is a story which I shall tell in my upcoming memoir-fantasie, “Scheherazade’s Sea: Wake Up in My Dreams”). I have become a well-known advocate of Autism and disabilities in my homeland, although this was never what I really wanted to do, but I did it anyway because there was nobody to stand in that gap at the time. I have won many public awards and accolades for my professional work and my voluntary contributions to my country and community, sat in boards of directors and co-founded charities and organisations for persons with disabilities, etc. My CV is so full, it is bursting at the seams and I have to mercilessly edit it, leaving vast chunks of information out.

Yet, nobody — neither Doris Day, elders in my family, nor school teachers, who were supposed to be caring for and nurturing me — ever taught me concrete and empowering ways to navigate the human normative realm and the complex (to me) layers of its social structures. I learned how to “behave” socially, but was never taught how to protect myself against the dark side of neuronormativity. In my personal life, away from the bright stage lights, I remained just as helpless, if not more so, than any other Autistic person without my impressive normative social performance, grandiose worldly accomplishments and many educational degrees. This insidious “hidden disability” has repeatedly thrown me into vulnerable situations, where I have fallen victim to social abuse time after time, and then offered no supports because either nobody believed that I needed any help at all, or I did not know how to or that I could even ask for help.

ABA and behaviour-focused interventions do not prepare the Autistic person for the kind of aggressive, violent and confusing Neurocolonialism that we have to face, in our struggle to navigate neuronomative realms.

All Autistic persons need support. It is both a difference in neurological functioning and a disability at the same time, especially in the face of overwhelming and confusing neuronormativity. Why is it Autistics are not taught basic survival strategies, such that we can be encouraged to thrive according to our intrinsic and organic functionality and abilities? And I don’t mean cooking, sewing, cleaning and “independent living”, which I am supremely well able to do if there were no human beings to intrude upon my Clement Space, presenting social conundrums that caused me grief. My “socialisation” was based solely on behaviour alone. Nothing else. I was punished for being “difficult” and “contrary”, but never taught how to identify, navigate and protect myself from insidious assaults on not only my personal dignity, but more fundamentally crucial, how to execute essential basic functionality in the oppressive, repressive and assaultive neuronormative world with its complex, confusing twisting, turning structures. Not even after my official diagnosis. All I learned from the psychologist who diagnosed me in my forties was what was “wrong” about me, and how I should behave in order to “perform” the “correct” way in normative society. I was also advised to seek a psychiatrist’s help for medication, which I recognise that some / many Autistic people do need to help them with severe anxiety, but it was the way in which the psychologist recommended it that brought shivers down my Autistic spine. ABA / behaviourism teaches us Autistics how to be good circus animals in an arena that is not ours to own. Even the most benign, “kindly,” or watered-down versions of ABA (whatever else they may call it) focus largely on behaviour, but of course they do so in gentler ways, and kudos to them for recognising the need to be a little nicer to us in the course of this “training”!

Even dog training is now moving away from traditional behaviourism, and considering the internal states of the dog as a sentient being worthy of dignity and autonomous thinking and feeling. The new aim is for the dog to thrive within our human world. Not simply behave the way we humans want it to. Why are Autistic people still subjected to ABA?

Instead of making us acquire superficial behaviours with no deeper understanding of normative social systems, Autistic people ought to be supported from a very young age to learn how to navigate neuronormativity in ways that are most optimal for our native Autistic paradigm. Foremost in my own sphere of lived-experience is, how to discern normative deceit in various contexts, from the personal to the professional and even financial. Ah, that wretched Sally Ann Experiment! I failed it miserably without even taking the test. And no, it is not about empathy at all. The “lack of empathy” accusation has long been debunked, yet it is still being bandied around. What I desperately needed was to learn how to discern normative-style insidious, intentional subterfuge. It’s not that Autistic people don’t lie, we are not all pure innocent beings, we are human too, and all humans are capable of lying and cheating. In fact, to be honest, I have met some rather unsavoury Autistic people in the course of my six decades of existence. It’s just that Autistics do so differently, and being Autistic myself, I am well able to spot it and deal with it accordingly. As for the normative, I cannot recount the many times I have been sold pigs in a poke, in very very dark, murky, smelly alleys.

Additionally, what people call the “spiky profile” phenomenon renders me helplessly inept at some most basic functions while quite abruptly tossing me high up onto various pedestals of brilliance that I never personally even wanted to stand on. I fought hard and passionately against grave odds to pursue my dream PhD — but that was all I wanted to do. Winning the top award that year was the icing on the cake, but I did not even know such an award existed until I was told I had won it. The process mattered far more to me than the outcome. While many PhD students complain about the terrible challenges, which are real, my PhD years were the best years of my life. I was engaging deeply in my passion, supported by a small scholarship stipend and with help from my youngest sister and loyal friends, and I had Lucy Like-a-Charm by my side. What more could I ask for? I most definitely did not ask for the other trappings or side-effects that came with my worldly “triumphs”. The latter brought me normative-style “glory”, but also heaped upon me a great deal of other people’s jealousy, oppression, repression, which I struggled to cope with, and ultimately did not help me to gain the peaceful, unobtrusive stability that I truly wanted at the core of my Autistic Being. I had mastered the art of performativity, but I was never empowered to live my best Autistic life in the midst of harsh, alienating neuronormativity. I had to learn how to “survive” one painful step at a time, making mistake after mistake, being crushed at so many turns and then getting up and keeping on keeping on regardless.

Everyone loves a dramatic story, and my life journey has been full of Artaudian-Wagnerian theatrics with massive sonic impositions. A little joke I share with a former mentor of mine, who became a close and trusted friend, is that I have led and continue to live a “weird and wonderful” life.

A little digression here, to explain my use of the term “weird”, which I know has become quite contentious nowadays. I grew up with the idea that eccentricity / weirdness was a positive trait to be proud of. I always knew I was somewhat “off kilter”, different, “odd,” and instead of berating myself about it, I was, deep down inside, very proud of being so. To me, it was a precious part of my identity that I stubbornly did not want to give up. No matter how well I learned all the superficial personifications necessary for normative social interaction, no matter how hurtful the criticism and excoriation, I felt no inner shame about being “weird”. Au contraire, I leveraged on it to provide endless entertainment at social events. If I had to be subjected to the torture of social pretext, I might as well make it fabulous!

Amidst the brouhaha of the Grand Circus of Performativity, I fell prey to all kinds of unsavoury social overtures. People — disabled and non-disabled — offered me sob-stories about their plight, and I would easily capitulate. I have ignorantly parted with vast sums of money this way, and once even opened my home to a particularly vicious con-woman. I found this woman sitting on the kerb on Christmas Eve in 2013, crying and moaning, dragging a sweet little dog on leash. She told me she had no home to stay in for Christmas, but she had already signed a lease and would move into her new home in two weeks time. I was deceived by her tears and felt sad for her little dog, so I told her she could stay in my spare room for two weeks. Well, she came with all her earthly belongings and then boldly refused to leave. She tormented me with her filthy habits, brought a loudly squawking parrot in a cage, and I found out that her poor little dog was riddled with fleas. My home became infested with noise, dirt, and parasites, which she had the audacity to blame on me! She even seriously maimed an innocent Greyhound dog named Panda, whom I was fostering and had naively allowed her to adopt. I even helped her to raise funds for the poor dog’s medical care after the terrible accident, which was caused by her neglect, but she pocketed the entire amount without paying the vet a single cent, and eventually even made off with my brand new washing machine and refrigerator, and of course refused to repay the loans she asked from me. I also dated men who were mentally and emotionally abusive, and again, took money from me. I gave generously to people who seemed to need help and support, but who turned out to be deceitful. I helped a blind woman with a guide dog, who complained incessantly to me about ill-treatment at the hands of her family and others. Her dog did not have a bed? I made one for her. Her dog needed urgent vet care? I immediately pulled out all stops to get her an urgent weekend appointment with one of Singapore’s top veterinarians. She needed medication and supplements for her dog? I procured them for her. I even lent her money too.

Is subterfuge a dominant neuronormative social trait, I wonder?

It seems to be so to me, after almost sixty years of wading through the mire. More recently, I was subjected to sensory torture at a most vulnerable time of grief and depression, trapped in a blistering cold room, shivering, with a pounding headache and fever, subjected to a verbal deluge for hours and hours of financial language which I could not understand, and coerced into buying a financial product which I neither wanted nor needed, where the actual terms were deliberately hidden from me. Throughout this ordeal, I had honestly and openly revealed my Autism and medical disabilities, as well as my present mental and physical state to the person, thinking I could trust him because he said he was trustworthy — “trust me!” he repeatedly declared to me, and I complied, I trusted him. Was this the wrong way to go about it? I now know it was, most surely. But I knew no other way, especially in that severely disabled and vulnerable state. Autistic trust is a well documented disability when not directed in the “right” way where it comes to neuronormative social wiles. I was like a deer trapped by the bright headlights of a thunderous lorry, charging straight at me, frozen in a catatonic state, unable to activate any fight or flight response.

Apart from stripping the Autistic person of dignity and autonomy, at its raw, basic foundation, behaviourism forces compliance in a way that makes the Autistic person shut down whatever little innate survival instincts that we may possess. We are trapped and rendered hapless. We cannot even flee, because behaviourism has inculcated into our psyches that it is “rude” to walk out of any social situation. We are groomed to be “polite” and “agreeable” at all cost to selfhood, without being taught to watch out and prepare for the evil and exploitative pitfalls that exist in the normative realm. Autistic people are thus completely disarmed, and helpless, like brow beaten circus animals dancing to the whips of tyrannical normative ring masters.

Nevertheless, despite the terrors of normativity, my life has also been truly wonderful, thanks to key people who came my way during the darkest valleys. I was blessed with loyal friends who stood by me when I was being persecuted by those who were supposed to support me; older professional mentors, themselves unusual people (probably undiagnosed neurodivergent or Autistic), who helped me along at crucial moments and subsequently became friends, and, for ten wonderful years, I had the company, guidance and comfort of Lucy Like-a-Charm. My relationship with Lucy was not merely a sentimental bonding between a lonely human and a pet dog. I have had pets at various points of my life, all of whom I truly loved. But Lucy was my creative muse and the one love of my life. No other entity, whether human or non-human, ever came close to the kind of symbiosis that I shared with Lucy. And none ever will.

You may ask, why did I fall prey so many times to normative evil and abuse, when I did indeed have support from friends, allies and mentors? Actually, even Lucy tried to warn me many times about unpleasant characters, but I, being the absurdly obtuse human steeped in behaviour modification, failed time and time again to catch her subtle canine cues, until it was too late. The truthful simple answer is, I did not know I was in perilous situations until I had fallen into the abyss. Then, I did not know how to ask for help. I did not even know that I could ask for help. I was taught, thanks to behaviourism, to firstly behave in a compliant manner, and then to handle my own problems myself, to stop “being a baby”, to not be a “princess”, to “suck it up” and be “resilient”. It was not until I had reached breaking point that my wonderful supporters even knew that I was in trouble, and dragged me out of the thick smoggy bogs that had sucked me in. Powerfully ingrained into me was the false and harmful notion that asking for help would make me a “nuisance” and I must never “trouble” or “inconvenience” others in so doing.

I will end my rambling about the ills of behaviourism with this true story told in Fantasia style.

A long, long time ago, in a far, far, far away land there lived little Princess bunnyblu. She could never get along with her mother, the Empress, and was groomed from a young age to become pampered slave to the eldest Grand Princess Winona, kept inside a luxurious Golden Cage. After many tumultuous years, Princess bunnyblu finally broke away, willing at last to risk even death, in order to find her Self again.

Princess bunnyblu thus became Scheherazade, the emancipated Autistic Woman.

Empowered, after several years pursuing her own dreams, Scheherazade returned home to the Empress, and began a reconciliation effort with the age-ing Empress. It was excruciating, but Scheherazade achieved her mission after much arduous and humbling effort, and of course, the Empress cooperated too, mellowing towards Scheherazade at the end of her life. Scheherazade was glad to have done so, because they parted in peace when the Empress died.

During one of many honest conversations between Scheherazade and the old Empress, Scheherazade asked why the Empress had always favoured the older two Princesses, Winona and Joanna, above Princess bunnyblu and the youngest Princess Little Marsh Flower.

Scheherazade pointed out that in all the bitter arguments and fights the Princesses had with the Empress, Princess bunnyblu and Princess Little Marsh Flower had never once resorted to physical violence against the Empress. In contrast, the older two Princesses had. Princess bunnyblu once witnessed Winona throw a glass bottle full of chilli sauce at the Empress, narrowly missing her by a few inches as it hit the ground and exploded into bright red slimy smithereens. And the Empress herself told Scheherazade that during an argument with Joanna, the latter tossed a hot bowl of noodles at the Empress, but fortunately also missed the Empress by a hare’s breadth.

Why did the Empress still prefer Winona and Joanna?

The Empress replied, “Because they never gave me any trouble.”

The Empress was referring to external social niceties, the Grand Pretext of normative behaviour. According to the Empress, Princesses bunnyblu and Little Marsh Flower were “badly behaved” at school, which brought “shame” and “embarrassment” to the Empress. It was all about external behaviour after all, nothing about love, care, respect and honour.

Behaviourism teaches the performance of normative pretence for the benefit of normative comfort, while rendering Autistics hapless against normative evil, with no benefit at all to the Autistic. And this is why I am against it, above all other reasons.

The normative world has much to offer in terms of realistic practical support to the Autistic. Why is this not happening, even now? Why is scientific evidence against ABA still being ignored, and meanwhile, nothing else cogently concrete is being offered in its place? Autistic people have risen up to try and teach the normative about our Autistic paradigm. Why is this reaching out for connection not reciprocated by the normative?

There is a Proverb that says, “Guard your hearts above all else, for it is the wellspring of life.” Autistic people need to be taught to literally guard their hearts, minds, and bodies, to be made aware of normative evil, as well as how to tap into normative goodness for support and survival, and even to thrive. Let’s ditch the behaviourism and focus on this, shall we? Why not?

Pingback: Bad Behaviour? – Scheherazade's Sea: Wake Up in My Dreams!